Some Words In Memory of Steven Spurrier

It is with deep sadness that I learn of Steven Spurrier’s passing. I didn’t know Steven well, but we met a few times, and he has always been the greatest inspiration to me.

I first met him at the annual Beaujolais tasting, which I used to organise while working with Westbury Communications, my first job in the London wine trade. Steven really, really loved Beaujolais, singing the region’s praises. He would taste every wine in the room with a smile on his face, taking careful notes in his notebook. Of course, he achieved more in his lifetime than most of us can dream of achieving—a celebrity in the wine world—but he was so humble. He would always send us very kind follow-up messages, thanking us politely for the opportunity to taste the wines, and commenting on some of his favourites. Not many people write thank you notes these days, but Steven always did. He was such a gentleman.

When I first spoke with him at our Beaujolais Cru focus tasting in 2017 at Dvine Cellars, he told me tales of his road trips through the region in the 60s with glistening eyes and a big, wistful smile. I noticed then that he smiled with his eyes when he spoke about wine. He spoke not of winemaking technicalities, but rather about how the wines made him feel; the emotions and the memories they evoked. It was captivating to listen to him; here was a man who truly loved wine.

Steven Spurrier at the Cru Beaujolais tasting in 2017

Pascaline Lepeltier & Steven Spurrier

It was also a very open-minded love; one without judgement or preconceptions.

In 2019, at my last tasting with Westbury, we poured several wines and pét-nats from the likes of Riesling and Cabernet Franc, but also from the vitis Labrusca x vitis Vinifera varieties found in New York State. Steven met Pascaline Lepeltier to taste her Chëpìka pét-nats produced from the varieties Catawba and Delaware.

While the wines made with ‘hybrid’ varieties like these have often been frowned upon by the traditional wine press, that was not the case for Steven. In fact, his reaction was the polar opposite. He swirled his glass in that slow, methodical way of his, and tasted and listened to Pascaline with joyous fascination, nodding enthusiastically and attentively.

Afterwards, he said to me,

“My goodness. What a revelation. Such interesting and delightful wines!”

I beamed in agreement; here was someone else who shared my passion for these unusual, intriguing flavours and embraced them for their uniqueness and individuality.

A month later, it was almost my five-year anniversary at Westbury. I had loved my time working there, but had decided to pursue my lifelong dream of being a writer. I plucked up the courage to email him to ask if we could meet to discuss the world of wine writing. He so kindly took me to lunch at 67 Pall Mall, & we spoke about the joys of wine. He listened to my ambitions for what would become LITTLEWINE, and he encouraged me. I asked him about his own journey; what had inspired him when he’d just been starting out, and what inspired him now? He said,

“Wine is a kaleidoscope. You look into it once and you can never go back to that moment. It always changes.”

He had such a poetic way of speaking about wine. This particular sentence made me smile, and I have it saved on my phone to always look back at. It summarised Steven’s humble approach to wine exploration and explained why his enthusiasm never waned. He was forever chasing those new beams of light cast by the kaleidoscope of wine, and storing the new memories that came with them.

When we said our goodbyes after that lunch, he wished me luck and said,

“It was lovely to see you and hear of your plans. How good to be 27 years old!”

I went on a walk today and sat down in an open field, and cried. It’s been one of those quintessential English spring days; perpetual blue skies, daffodils and birdsong. As I click the button to publish this, it has just turned 6pm and it’s still not dark. It’s been the sort of day that embodies Steven; a spring day in memory of a springlike person. He was 27 years old, too—at heart and in spirit.

Sitting in that field, I thought about why he was so important to me. I realised it was because he had an unparalleled positive energy; the sort of vibrational energy that you can’t help but be affected by if you share the same passion. The way he spoke about those Beaujolais wines the first time I met him set something alight deep in my belly. Part of the reason I love wine so much today is due to Steven’s love for wine. It was utterly infectious, and his words of encouragement gave me confidence to do what I do today. It meant so much to me.

He will be missed by so many of us. We owe it to Steven to spread his unconditional love for wine far and wide, so that others may come to love wine as much as he did, too.

With Steven in 2018 getting my copy of ‘Steven Spurrier — Wine, a Way of Life’ signed

NEW BEGINNINGS, MY JOURNEY THUS FAR, BEING KIND, CHANCE & FATE

2019 is most definitely proving itself to be the Year Of New Beginnings and Leaps of Faith.

2012 saw my initial entrance into the world of wine - I moved to Beaune as a stagiaire for Louis Latour on my year abroad (I studied French at the University of Exeter). 2013 was occupied by my thesis writing at university, the title of which was To what extend did the monks of Burgundy influence modern day wine, a piece of writing I had so much fun compiling and that cemented my admiration of the wine world (I was fortunate enough to handle a bunch of Medieval manuscripts in the Beaune archives).

2014 saw me move to London, to Cricklewood of all places with university friends (don’t go there - seriously, there is absolutely nothing there, but it was cheap rent and we had a garden), and I joined Westbury Communications as an intern. I chose Westbury as I had enjoyed my PR work at Latour, and I loved wine. I didn’t even know wine PR was a thing, I simply googled “wine PR London” and up popped Westbury, Phipps and R+R. I chose Westbury as I bonded with Sue Harris, MD, in my interview, and at the time, Westbury had Beaujolais as a client, a region I already adored. I didn’t know what the on and off trade meant, and I don’t think I knew how to pronounce Chianti.

I took to the job like a duck to water, and loved every minute I spent with Sue and the team (apart from the time a journalist made me cry. Not to self: be kind ALWAYS, and never make PRs cry).

The same month I joined Westbury, I started a wine blog called vintageofallkinds.co.uk (now defunct). It was so named because I wrote about both wine and vintage clothes. My boyfriend at the time (now ex), told me once, “wine isn’t very cool, why don’t you do music PR?” I seriously considered it - I was rather under his spell and when you are in a morally questionable relationship it does strange things to your mind. Thank GOODNESS I didn’t leave the wine trade.

I loved writing about wine. I have always written - when I was nine years old I wrote a “series” of “books” (they were around 30 pages each) about a horse called Firefly. I’m fairly certain the font size was closer to 22 than 11, but it was a start - I was hooked on writing. I went on to win lots of creative writing competitions at school, which spurred me on to choose French literature at university, which I adored - everything from Camus to Marie Darrieussecq - the latter wrote a feminist masterpiece entitled Pig Tales - a Novel of Lust and Transformation. It is the single most Fucked Up & Brilliant book I have ever read. I was mesmerised by the power of words.

Vintageofallkinds had about 20 readers (nearly all of whom were my family) for about a year. Then, in the summer of 2016, The Buyer launched. Sue and I went to the launch party, and we sat and had a glass of Champagne. Sue asked me what my career dreams were, and I cocked my head to one side and admitted, “well, I’ve always wanted to be a writer.” She took me by the arm and introduced me to Richard Siddle, one of the cofounders of The Buyer, and said, “Christina would love to write. Just introducing you.”

I shyly muttered to Richard something along the lines of, “umm.. well.. I’d uh… I’d really like to write something to send to you, if you might have a look… don’t worry if not,” etc. Richard said, “go on, send us something,” so - I did, and it was published.

That was really the beginning. I went on to write several pieces for The Buyer, all of which I’m still proud of, even though I do cringe a bit at my early writing. It’s difficult as a writer to find “your tone” - it is something I that I believe is born out of confidence, (but never arrogance), and when I started I had very little confidence.

Writing and my PR job lent itself to travelling, so I was off - all round the world - I was completely and utterly hooked. From having my hands in the dirt with Eben Sadie in the Swartland, to sitting in a snowy mid-winter Styria around the dinner table with Ewald Tscheppe, Sepp Muster, Andreas Tscheppe and Margaret Rand pondering The Greatness of Wine, to drinking old Barolo in Burgundy with Diana & Jeremy Seysses, to my first times stomping grapes with Johan Meyer in the same bin of Touriga Nacional that my best friend Imogen Taylor fell into, to drinking Abe Schoener’s first vintage (1999) out of magnum at Swan Lake, to standing on Raj & Sashi’s plot of seedlings, to navigating the serpentine cellars of Kongsgaard, to dining solo all around the world, there have been so many moments where I’ve marvelled not only at the beauty of wine, but at the kindness and generosity it gives birth to in the people that care about it.

With Sepp, Ewald and Andreas, January 2018

I am so fortunate to have had the kindest, most supportive mentors from the beginning. Sue Harris, Peter Dean, Richard Siddle, Jamie Goode, Mark Andrew & Doug Wregg - I wouldn’t be where I am today without you. The key word here is kindness. They have smothered me in kindness, honesty and constructive criticism since Day One.

I clearly remember a couple of years ago writing a rather dogmatic piece about terroir, and receiving some pretty sharp criticism, and being quite upset by it. Jamie & I spoke, and he said, “Never Complain, Never Explain.” It remains my mantra. As writers, we put thoughts, notions and opinions out there for the world to see, so we are very open to criticism. Having someone criticise a piece of yours can feel a bit like someone ripping out a page of your notebook, crumpling it up and shooting it into the fire, but hey - if someone reacts that way, you’ve engaged with them - and that is A Good Thing.

I launched christinaramussen.co around the same time. This became my home to all sorts of musings, as well as a place to put my published pieces. People started to engage with my writing, and I was pretty shocked - (woah - people actually like what I write?), and so encouraged. This gave birth to more writing, which in turn gave birth to more approaches by the likes of Les Caves, Sprudge, Bibendum, Tim Atkin MW et al.

After four and a half years at Westbury writing in my spare time like a crazed sleepless wine obsessed pencil clutching madwoman, friend and co-founder of Newcomer Wines, Daniela Pillhofer, approached me with the idea of launching a new company.

She said, “I’d love for you to contribute, or to become a partner in the company, or anything in between.”

The role would involve me becoming a full-time journalist, editor and art director all rolled into one. She would become CEO & CFO, which led me to sigh with relief for I can barely do simple sums.

She is, by nature, an entrepreneur, and that means I’m now also an entrepreneur! Who would have thought?!

Suffice to say, my answer was something along the lines of, “Hell Yes.”

The company will be a new platform for wine content (that’s all we’re saying for now). We began building it two weeks ago, and we aim to launch in October/November.

In the meantime, I’ll also be jetting off to California in July to do harvest for the first time with the inimitable Abe Schoener, in Los Angeles, on a site that was a winery in the 1800s, to finally learn how to make wine (books can’t teach you these things).

If you had told me all of this in 2016, I would have gawped at you, but as I sit here now, I feel calm, content, and truly happy. We need to take these leaps of faith in life - because, simply put, we do have just one life.

Whether all of the above happened by chance, or if it was somehow in the stars, I don’t know. What I do know, is that we must follow our own conviction, and take chances and risks if we are to find true contentment. Imagine if I had been sitting at a desk at a music PR firm, thinking, “what would have happened if I’d stayed in wine?”

I cannot wait to see what the future holds, and I cannot wait to make mistakes, and to learn from them, and to grow with our new little seedling of a company. I cannot wait to support younger people coming into the industry, and I hope to inspire people with our content, and to spread our love of wine as far as we can.

In the meantime, this website will be home to my contemplations and reflections. All the wine geekery and enthusiasm will be stored up in a notebook (or should I say GoogleDrives), ready to launch with the new company later this year.

Wine Love & Kindness,

C x

PLEASE SIGN & SAVE SÉBASTIEN DAVID’S WINE #sauvonscoef16

Sébastien David’s Hurluberlu cuvée is a bottle that has become emblematic of a global coalition of winemakers striving to work to create wines made environmentally, with soul, and that specific bottle lines countless windows of wine bars whose owners and sommeliers wholeheartedly support said movement.

He comes from a long line of winemakers (15th generation), creating expressive wines in Bourgeuil from fifteen biodynamic hectares. Wines, like farming, are chemical-free – indigenous yeasts, whole cluster, low / no sulphur. He has arguably been one of the driving forces behind the Loire’s surge in organic and biodynamic growers.

So how is it that he is being forced to pour away 2,078 bottles of his lovingly tended Coëf cuvée?

Via this article on Change, I’ve been alerted to the following and am paraphrasing below:

Difficulties and disagreements between growers and the INAO and various regional tasting/testing bodies have long been documented (Alexandre Bain and Jules Desjourneys’ infamous Interdit cuvée ring a bell, anyone?), however rarely do cases go as far as to demand the expulsion of certain wines from even vin de France.

In this case, from what I can gather, French administrators recorded levels of volatile acidity in the Coëf cuvée that were higher than permitted. However, organoleptically a technician stated it was acceptable, and Sébastien proceeded to carry out his own two counter-analyses, which came back at acceptable levels.

According to the Change petition, the measuring instrument used by the BIEV was sold to them by the laboratory where Sébastien carried out the counter-analyses. The technicians of the latter laboratory stated, "it was not the first time that an employee of the BIEV did not use the device correctly…”

I’m grimacing. Are you?

Despite the results of the two counter-analysis, the administration sealed his batch of 2,078 bottles and the prefect of Indre and Loire, Corinne Orzechowski (pref-secretariat-prefet @ indre-et-loire.gouv.fr) asked via a decree, to destroy his batch of 2,078 bottles within a month.

Sébastien has raised an urgent court case, of which the hearing will take place next Friday, May 10th at 11am at the Administrative Court of Orléans.

It goes without saying the financial issues this would cause a small grower. To work biodynamically is expensive (not to mention the Italian amphorae that house this wine), and this is Sébastien’s livelihood at risk.

How is it that chemically farmed wines from vineyards that are near herbicided-to-death pass, and one wine that sits on the fence of volatility is potentially to be poured away, despite the fact that its vineyard is home to happy, healthy, fifty-year-old biodynamic Cabernet Franc vines?

PLEASE sign the petition, and come party with me when Coëf 2016 is released.

Blind Tasting with Rajat Parr

Raj, the Jura, February 2019

Blind tasting. One of my favourite activities in the world. Maybe even my favourite. Tied in first place with padding along the beach in North Denmark.

I will never forget the first time I met Rajat Parr. The entire evening is etched in my memory. I had heard on the grapevine that he was a pretty good taster. Pretty good to say the least. Phrases like “the best blind taster in the world” had been thrown around. So, his reputation preceded him. It’s difficult to know how much truth lies in rumours like these, and I wasn’t sceptical, but I was curious to see whether he really was that good or whether it had been exaggerated.

I was coming back from Burgundy a couple of years ago. My plane was delayed by two hours, so I landed at 8pm instead of 6pm and I was particularly exhausted. Michael Sager texted me when I landed and said, “come to Hackney Road, Raj is in town and you need to meet him.” I very almost didn’t go but Michael persisted and just said “come on!!!” so I dragged my tired butt onto the train and out to Hoxton.

There is an amazing little wine shop in Chassagne-Montrachet – Caveau de Chassagne – that has a separate list if you ask nicely, where there are all sorts of incredible wines hiding – think Henri Jayer old vintages for dayzzzzz. I can’t exactly afford Jayer, but there’s also a great Rhône list and on that trip, I had spied a bottle of Hermitage blanc by Guigal, in my birth year – 1991. It was only around 40 euros so it got stashed in my suitcase straightaway.

I didn’t know at the time that this would be serendipitous and that that bottle would be the wine that would define one of the most important vinous memories of my life.

I had originally planned to drink it with my dad (sorry dad) but when I arrived at Sager + Wilde and was introduced to Raj, Michael whispered to me, “let’s blind him on something!”

So, instead of choosing something from the list, I got that bottle out of my suitcase behind the bar.

Michael and I gave a glass to Raj and leant back, like excited school children waiting to see who got the lead in the school play.

Raj swirled the wine glass in his hand absentmindedly, chatting with us, took a sniff and instantly said, “Hermitage.” He hadn’t even tasted the wine.

He took a sip, and said “Guigal. Early 90s.”

My brain exploded. I was completely and utterly speechless. Dumbfounded. It was the perfect way to meet someone who has today become such a dear friend and mentor. It is perhaps the single moment that told me, you are on this path for good. That was it. I was hooked. Transfixed. Obsessed. This is not a drill.

When we showed him the bottle, there was no celebrating, just a small smile and a shrug. Raj is an incredibly humble man and he reflects the importance of humility in the face of wine.

I can only aspire to one day be sitting in a wine bar, to be introduced to someone just embarking upon their career, to be challenged to a blind tasting of their birth year wine and to nail it casually in one go.

Raj, thank you.

The Importance of Solo Dining, feat. The Glue Pot & Le Bocal

Et cela sera pour combien de personnes?

Qu’une personne s’il vous plaît.

Many of us city dwellers lead rather chaotic, fast & furious lives (by furious here I mean full of energy, as opposed to anger). Those of us in the wine trade have the advantage of leading a life where work and pleasure somehow become inextricably intertwined; a blessing, but also one that means we can end up burning the candle at both ends.

I discovered the joys of solo dining by necessity when I packed my bags and moved to Beaune six years ago as a bright eyed and bushy tailed 21-year-old. My budget was much smaller then than it is now (saying that it’s still not huge - hello wine trade) but I had almost no friends in Burgundy at that time (save for my dear friend Edouard Maurisset-Latour who pretty much saved me from an existence of intense loneliness), so when Edouard wasn’t around I would occasionally traipse down the 16th century steps of my apartment and explore the gastronomic streets of Beaune by night.

I quickly realised that solo dining wasn’t scary at all; in fact, it was deeply soothing. I sat in many restaurants and watched the world go by - watching fellow diners and coming and going, conversations full of laughter, joy, and sometimes neither. At the same time, I would be taking in everything about that restaurant all alone. Of course, dining with companions is equally as enjoyable - I’m not a total loner - but the companion in question will take at least 75% of your attention. Alone, the restaurant is allowed 100% of your attention, and in return, it gifts you much needed time to your own thoughts.

This weekend I was in Champagne for the first time, alone, to visit Adrien Dhont and Timothée Stroebel. I headed to Le Bocal on Friday night, the most adorable miniscule fish restaurant behind the fish market, which I found via an article by Peter Liem. I ate homard bleu and drank biodynamic Les Meuniers de Clémence by Lelarge Pugeot. A pairing from another universe where lobsters and Champagne bottles roam hand in hand. Bliss. The service was impeccable and the butter was something divine - no idea what was in it but I think some kind of fish roe. If you are a fan of fish and Champagne, this place won’t let you down.

Le Bocal, Reims

The second night, Adrien told me “go to The Glue Pot. It’s like an English pub, but not, with an epic wine list.” Weird, I thought, but sure, I’ll go with it.

I had some work to do, so went back to my Airbnb and headed out at 21:15, without a reservation.

Mon dieu.

I walked in and wondered whether someone had slipped some acid into my coffee earlier. RED. So much red. Red carpets, red leather chairs, red walls. Errrrthing red. Based on a (shit) English pub - it looks even more like a (shit) English pub from the outside, with a DJ bashing out pretty good electronic music, but with acoustics that are so good that nothing seemed too loud or blare-y. TVs showing what I can only assume to be some very strange talent show with people riding penny farthings and doing intense acrobatics on hover boards. Handstands and splits galore. Fucking fascinating watching, I’m not going to lie. I was glued, no pun intended.

The Glue Pot, Reims

The service - some of the best service I’ve ever had, brilliant and caring staff and Stephan, the owner, is such a character and knows his wine inside out.

Now, the most important part: THE WINE LIST. Not going to spoil it for you but go and you shall not be disappointed. Some of the most interesting cuvées and best prices I’ve ever seen in a restaurant.

The food. Exactly what I needed after a long day of tasting. The most delicious camembert deep fried snacks - it’s actually really hard to get deep frying right without being greasy. These were perfect - crisp and so fresh. Next, the most tender, mouth-melting veal I’ve had, with glorious nutty comte cheese which was the pairing from the heavens with Clos Rougeard’s Brézé Blanc 2011 - not exactly a wine you get to drink every day.

___

I try to dine alone at least once a month. It almost verges on therapy for me. It is one of my favourite activities in the world. I have many friends who find the idea weird or even scary; I just hope by writing this perhaps some of the solo dining doubters out there might give it a go. I’m sure it’s not for everyone, but go on - have a try. You might be surprised and you might even start joining me in making some of those “Reservation for one, please.”

Peter-Allan Finlayson on Terroir

Peter-Allan, P-A for short, is one of South Africa’s most talented winemakers. By that, I mean that he is one of the very best at conveying what the site in question gives us, to the final glass.

During a recent, particularly vinous “off duty” dinner at Noble Rot featuring older vintages of Leroy (say waaah), I stopped and got my notebook out because wine, after all, can be the lubricant to Great Chat, and this was an interesting one.

The wine that started this particular Great Chat was the Gabriëlskloof Syrah on Sandstone. It’s a really serious wine that totally bowled me over. Bright, savoury and pure with tons of energy and lift, with a lovely ever-so-subtle warmness on the mid palate that would otherwise land me right in Côte-Rôtie territory. There are gentle wild flower notes, violets and irises, with dried herbs and lots of peppery characters lifting the finish with a real oomph - particularly white and pink peppercorns shine through. There is less fruit as opposed to “other” characters here - rockiness and smoky reduction give the wine its shoulders, and there is an amazing, mouthcoating crumbly texture that definitely appears to come from somewhere.

But where? That is the question.

P-A begins by explaining that the sandstone creates vines with half the trunk diameter of the vines from the cuvee that sits on shale (the cuvee of which is named, funnily enough, Syrah on Shale) due to extra water stress. He believes this imparts more of these savoury notes onto the wine, particularly the pepper.

Meanwhile the shale cuvee has 30-50% clay in its soils, which means the plant grows faster, producing more dark fruited, earthy and inky wines, in a way comparable to Cornas.

He continues, “I often believe terroir is actually a question of absence. What is absent from the soil (nutrient deficient soils for instance) naturally means the grape pulls what is best out of it, and it struggles - this struggle brings those spicy notes to the forefront.”

“The vine expresses what it is grown on, and the salinity translates this in the glass.”

“Look at the Mosel. Those soils are extremely stressful - there is no matter there, and they stress the Riesling. This means you get the most out of Riesling as a variety - the roots push deeper and deeper as they struggle to survive.”

Peter’s wines are imported by Liberty.

MERLOT: WHO'S YOUR MUMMY?

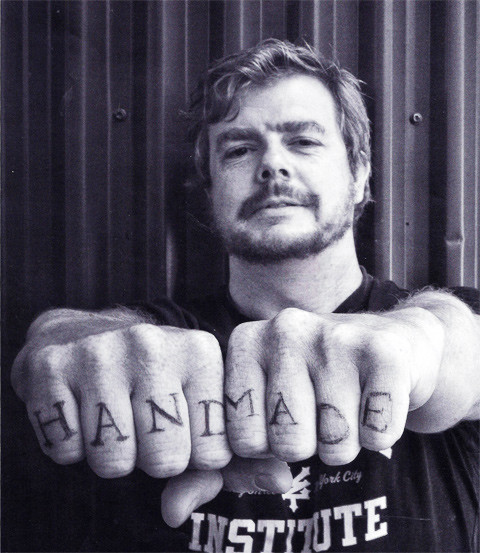

This photograph landed in my inbox this week and it might be the most excited I’ve ever been about an email. It doesn't look like much (let’s be honest), but it’s very special. What is it?

It’s Merlot’s Mum. She had been lost, and some thought she would never be found. She is now being grown (albeit only with three plants) by Clement Dubos in SW France.

If you had told my 20-year-old self, busy going out to as many music festivals as still getting a 2:1 in her French degree would allow, that she would be sitting down at age 27 to buy and download a research paper entitled Parentage of Merlot and related winegrape cultivars of southwestern France: discovery of the missing link, she probably would have given you the side-eye look of questioning, and a response resembling something like…

Yet here I am, at 27 years of age, head-over-heels with ampelography.

Ampelography is related to the identification of grapevine varieties and species. Why is that so important? Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding and José Vouillamoz included 1,368 varieties in their Wine Grapes bible (these are grapes specifically used to produce wine, outside of this there are thousands more).

So while it is clear we have hundreds of exciting options out there to make wine with, unfortunately, the modern day world appears to have fallen out of favour with variety in wine.

Ask a friend who doesn’t work in the industry what they like to drink, and I think the following wines are more often than not the answer:

Argentinean Malbec, Merlot, New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc, Australian Shiraz, Italian Pinot Grigio, Prosecco, Rioja, and for those that can afford it – Burgundy and Bordeaux.

Why is this a problem?

Let us start with why it’s not a problem. These countries/regions/varieties are successful for a reason; they have pushed for quality in some sense of the word and offer reliability. My own favourite region in the world is Burgundy and I drink a lot of it. I’m not going to tell myself or you to stop drinking the wine that you love and trust, just like I am not going to tell you to stop cooking your favourite comfort meal or ordering your favourite pizza.

However, let’s keep comparing it to food. Do you eat the same meal every day? The answer is likely not. Imagine how boring our culinary life would be if we walked into the supermarket and were faced with only aubergines and apples.

That’s not to say aubergines and apples don’t play an important factor in our lives; without them we wouldn’t be able to make parmigiana or tarte tatin.

But we don’t only have aubergines and apples. We have choice.

So why do so many always buy the same wine, or the same grape variety? Comfort perhaps; reliability. Bad experiences.

But our lack of exploration in wine, in humans, is leading us down a difficult and dangerous path.

A startling statistic tells us that the 20 most prominent grape varieties in France accounted for 91% of vineyard area in 2012, compared with 53% in 1958.

This means we are around 9% away from having only 20 grape varieties in France.

This is the vinous equivalent of us only having 20 ingredients available to use from France for our meals for the rest of our lives.

We have many things to blame for this, and I won’t delve too far into them. Phylloxera, financial stability, reliability, the globalisation of certain tastes and the creation of certain brands all have a role to play.

Historically, ampelography has relied on our human eyes and hands. We have looked at vine species and guessed as damn close as possible what they are, but we are not omnipotent, and we make mistakes. We were also unable to link varieties to one another.

Everything changed drastically in the early 2000s with the introduction of DNA testing for vines led by Carole Meredith at UC Davis in California. Drum roll please… suddenly we were able to create factual family trees of grape varieties. Grape geneticists quickly got to work.

One link had been missing for a while. We did not know who Merlot’s Mum was.

She was found one day growing up a building in the Southwest. After DNA testing, it turned out she was also the missing link for Malbec’s family tree; Merlot’s Mum is also Malbec’s Mum.

They named her Magdeleine Noire de Charentes.

Had it not been for this stray, ancient vine, Magdeleine, whose species had metaphorical sex with two lovers (in the form of grape varieties) back in Shakespearean times or before, and a grapevine stork dropped off two babies in Merlot and Malbec form, these two grape varieties would have never existed. Can you imagine? I can’t.

I had the pleasure of dining with Jean-Claude Berrouet in the summer of 2018 to taste the wonders that he is achieving with Merlot via Twomey across the pond from Bordeaux where he crafted one of the world’s most iconic wines; Pétrus. It is not an overstatement to say that we would not be living in the world of wine as it is today without Monsiuer Berrouet. We spoke about ampelography briefly. He asked me whether I know who Merlot’s mother was.

“But of course,” I answered. “She is Magdeleine Noire de Charentes. I’ve even named our wine tasting group after her.”

He smiled; it was the kind of smile that crinkles at the sides of the mouth and eyes, warming up the whole face.

It matters. Jean-Claude knows it matters. I know it matters. I hope we all know it matters. Plant diversity and genetic diversity is crucial in our world; there would be catastrophic consequences without it.

I asked Dr José Vouillamoz, Grape Geneticist and a huge inspiration to me, to comment,

He said, “In 2009, my colleagues at INRA in Montpellier have published the discovery of the missing link in the parentage of Merlot: it is a natural, spontaneous crossing between Cabernet Franc and Magdeleine Noire des Charentes. At the time of the discovery, only five vines of this plant were still in existence: one in northern Brittany growing in a forest, and four in the Charentes growing in front of farmhouses. This missing link was on the brink of extinction, yet it is the parent of the second most planted grape variety in the world. This illustrates the importance of conserving the old, obscure or minor grape varieties that are our heritage as well as a source of genetic diversity and a possible solution for climate change.”

Let us save Merlot’s Mum, let us look after her, nurture her, safeguard her and fix this predicament we find ourselves in. Merlot’s Mum is a metaphor for all indigenous varieties. I strongly believe that the combination of our ability to genetically test grape varieties, as well as a growing faith in our own varieties and individuality, are the reason that for the first time in many years indigenous is on the up. Indeed we can take it one step further; it is not only in their homes but also away from their homes; look at what young Jaimee Motley is achieving in California with the Savoyard gem, Mondeuse (Syrah’s grandparent!) I believe this will become one of the most exciting wines in the world. Winemakers have more love and trust in their local varieties and pour such energy and love into their cultivation that quality shines. As a result, suddenly we see the once lesser-known varieties pop up on the other side of the world.

So -this is a small plea for help from us. Next time you buy your wine, whether it be from an independent merchant, online, or in a supermarket, have a read and look for something different. Try a grape variety you don’t know; even better, try one you can’t pronounce. Ask the store staff for advice on indigenous grape varieties.

Tell me about the wine you find. Tell your friends about it. It might be the start of a lifetime of vinous exploration.

An Ode To Very, Very (Very) Old Wine: Tasting Bordeaux from 1881 to 1924

Wines, like people, come and go. Some become our best friends, some remain etched in our memories, and some get pushed to the bottom of the memories pile and resurface many years later; not unlike that friend you had when you were five who suddenly appears in your dreams for no reason. Others, quite simply, are forgotten forever and dissolve into nothingness.

There are bottles we buy with eager anticipation to open the same day. There are bottles we buy with the purpose of ageing, but open far too young because of impatience.

There are bottles that are opened at “perfect” maturity.

Then there are bottles that lie patiently waiting; ones that lie with ears pricked when their owner walks into the cellar.

“Hello! I’ve reached my peak drinking window according to the critics, it’s time to open me!!!” they shout, their voices muffled by their corks, but their owner leaves them snoozing on, so that eventually their journalistic drinking bracket has long expired and they fall into a deep slumber, having given up hope and wondering whether they shall ever see take a deep breath of oxygen into their liquid lungs again.

I recently attended a tasting where twenty-one of these wines were, as if by miracle, gently poked awake from their deep slumber. I’m not sure who was more surprised – me or the wines.

Dégustation Vieux Bordeaux took place on the 17th January. I will start by saying I cannot do these wines justice.

We must remain humble in the face of wine, and in the face of experience. Older wines, like our elders, have far, far many morestories than us to tell. It is up to us to listen to them. Without them, we know something; but that something is gravely stunted.

I cannot tell you about the vintages, and I cannot tell you how the châteaux were run at the time. Nor will I try.

I can, however, do my best to put into words how they tasted, and tell you how they made me feel.

I often speak about alive wine, and I like to think that alive wines sometimes choose to tell us their secrets. Most of these wines were alive, and many of these wines shared their secrets with me. Wouldn’t you want to share your secrets, if you had been told to sleep for between 138 and 95 years? These wines lived in another era; and they want to tell us about it.

1881 Château Léoville Poyferré (Averys bottling)

Alive and kicking; this was one of my favourites that I nuzzled in my glass for a very long time. Somehow still with a flickering and bright ruby core, it was clean and ever so pure on the palate; not unlike tasting the vinous equivalent of a fresh red wine-meets-water spring. There was black raspberry skin and packed black earth with dried tobacco leaves. Cherry stones lingered on the palate with a crunchy texture and oh – that acid. In old wines, acid seems to take on a personality of its own. There was an apple-like acidity of vibrancy. Once the acid settled, the wine showed its other feathers; tree bark and a sap-like delicacy with pine cones and apple pips. Fresh mint leaf made a gentle appearance on the finish. a fresh savoury wonder; so light on its feet; a vinous enchanted forest. After all; Hans Christian Anderson died only six years before its birth.

1907 Château Haut Bailly

Slumbering a little still; ashy, dense, dark and brooding. Cedar and ash, wood smoke and undergrowth. Less overt fruit here than with the 1881 but still showing remnants of its blackcurrant and bramble nature. Sooty woodiness but somehow finishing so bright. Slumbering but alive.

1911 Château Brane Cantenac

I have never, and I don’t think I will ever, taste anything like this again. Either the wine did die and it came back as a ghost, or it decided, “to hell with this waiting game!” and flamboyantly took on wine profiles that none of us had seen before. Regardless, its aromas were definitely kicking. Sour yoghurt – frozen yoghurt style, cocoa powder, chocolate chips. Mushroom dust. Blue cheese; even epoisses as one taster added.

1914 Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande

Oh, what a wine of powerful energy. A muscular, almost jagged, nose and structure; a beautifully confident structure. A thorny, mossy character on the palate, with truffles and dried porcini mushrooms chiming in. Savoury fruits of the forest suddenly awakened after a minute or so; as if to yell quietly - … we’re still here. It finished with black smoke; as if to say, now you see me, now you don’t.

1916 Château Smith Haut Lafitte

Only just alive; somewhat on its death bed. Soy sauce and dried hay and barnyard pull through, with a tangy, umami character, joined by a last leap of faith via dried flowers of a heathen nature. A gentle side of coal joins the finish which made me think the deathbed might be near.

1916 Château Gruaud Larose

Hello, you – very much alive and proud to be so. This wine has its morning suit on with a cigar in hand. Dense, smoky and savoury; nutmeg and cinnamon spice peeking their heads out here. Wild thyme and dried branches make an appearance, with a certain olive skin character that’s very appealing and lifts the palate of the wine. Lavender joins on the finish and the tannin structure falls onto the palate like gentle snowflakes. What a wine.

1916 Château Durfort Vivens

Bright and tangy with primary fruit still a gung-ho somehow. Some electric brightness here despite the lighter body; bramble skin and bramble leaf with direct vertical zippiness. Perhaps less characterful, but still lovely.

1918 Château Haut Bailly

Savoury and earthy on the nose; hot earth on a summer’s rainy day. Dust and white smoke; ashy, with less fruit, but the subtle blackcurrant pith that remains pokes its head through.

1918 Château Marquis de Terme

A bit volatile here. Not sure what happened here but I think we lost one to another world. Man down, RIP.

1918 Château Léoville-Las Cases

I cannot even describe what this wine gave to us. Giggles and eyes of astonishment appeared. Some looked puzzled, others looked enamoured. We all tried to reason with its aromas. This, amongst all of the wines, was the one with most personality. It certainly showed us its one-of-a-kind peacock feathers. I’m not even sure we can say peacock; this is a breed of its own – some sort of mythical bird. Pure blackcurrant juice met frozen bramble sorbet, which met some kind of black cherry liqueur which met blood orange confit. There was an outstanding amount of fruit here, and almost no tertiary character. Wine can defy all laws sometimes, and this wine was testament to that.

1919 Château La Lagune

Somewhat under the radar, this little one left me spellbound. Cigars and cedar on the nose suddenly lifted out of nowhere to bring blackberry pips and black cherry stones, with a confident side of spice; almost fiery and chilli like, with black and white pepper sprinklings. One of those rare wines to carry a rumbling energy from within.

1920 Le Tour de Tertre (?) - labelling confusion, unsure of this wine’s existence – is it a ghost?

The first of the wines to be led by graphite; a quality I greatly desire in Bordeaux. A hot summer night of tarmac and dust joins the nose, but not much fruit is here.

1920 Château Brane Cantenac

Goodness; just beautiful. Ethereal, pretty, elegant and dancing; in its ballet shoes. Truffles and fresh vanilla pods meet on the palate with fresh bramble fruit. Simply the definition of ethereal.

1922 Château Lanessan

Woody and minera, dustry tannic structure. Wild bark character, like sucking on wood. It may sound crazy but this tasted like a vine with an added side of tomato leaf.

1924 Château Pavie

1st corked, sob.

2nd - Graphite, black lead, woody and forest like. Bloody and metallic.

1924 Clos Fourtet

Plush, rich, savoury fruit, very powerful, weighty on palate, bur bright acid lift. Umami, sweet soy sauce. Bloody and meaty.

An enormous thank you goes to the wonderful, entirely inimitable, Roy Richards. Roy - thank you for this incredible generosity. I know you’ll probably shake your head and tell me to oh shush, but truly - the world of wine would be a much dimmer state without you. You were one of the key contributors to its shining state today.

If you’d like to read more about what he achieved and why we owe him one, Jancis wrote a brilliant piece here.

Gérard Basset by Nina Caplan

A shorter version of this article was published in the Masi Foundation’s Le Venezie magazine.

Gérard and Sandro Boscaini of Masi

The wine world doesn’t often have cause to be grateful to football, but were it not for the so-called “beautiful game” Gerard Basset might never have moved to England, discovered wine and his own talent for it, changed the way this country offers hospitality to travellers and given the English the reflected glory of being able to claim the world’s most qualified wine professional as our own. Basset, who is so charming and modest you might suppose he had barely a qualification to his name, is in fact the only Master of Wine (MW) who also possesses both a Master Sommelier and a Wine MBA qualification; he has also won the World Sommelier Championships. Best Sommelier in the World hardly seems the title for someone with is the opposite of boastful.

Basset, born in Saint-Etienne near Lyon and an avid supporter of the home team to this day, came over for an away game against Liverpool, 40 years ago. “I was 20 years old, delivering washing machines and TVs,” he remembers. “I thought England was just a place where people drank tea all the time and it never stopped raining, but in fact I really liked Liverpool.” He came back to work, and at 26 moved to England permanently and became a waiter, with a view to a career as a restaurant manager. Everyone in his new workplace assumed he knew all about wine because he was French, but in fact, he had grown up being served a little wine in his water (“it’s very refreshing”) but with nothing decent on the table. “Wine then was like salt,” he says. “You don’t look closely or get excited about different kinds unless you’re really geeky about salt, you just put it on your food”. A couple of times a year, his parents would buy something half-decent but other than that, they drank plonk – which was hardly the view of France from across the Channel. “There was a catering student who was moonlighting as a waitress a couple of evenings a week,” Gerard recalls. “She’d attended a lecture on wine and didn’t understand what noble rot was. I didn’t have a clue what she was talking about! I had to quickly buy a book so I could answer her questions.”

And that was how a Frenchman began his wine education in, of all places, England. He ended up Head Sommelier at luxury Hampshire hotel Chewton Glen, where he got on so well with manager Robin Hutson that when the latter decided to venture out on his own, he asked Gerard to be his business partner. “But I had no money! I had a 100% mortage on a flat I’d bought for £52,000 that was now worth £34,000. So I actually had less than no money. But Robin said don’t worry, I’ve got shareholders.”

They went down the road to Winchester, which had wealthy inhabitants and a brand new motorway, and opened a hotel that would start a revolution – although they didn’t realise that at the time. Hotel du Vin was informal but never basic; the rooms were comfortable, with fresh milk in the minibar, quilts and power showers, and the food and drink were, of course, fantastic. It was 1995. They would surely have succeeded anyway, but they got help from an unlikely source: a murderess. The trial of serial killer Rosemary West began just as they opened, in the Crown Court round the corner from the hotel, and the journalists reporting the trial kept them booked solid for months. “We had 13 bedrooms but had to keep one for ourselves as we had no night porter yet,” Gerard recalls. “Two we reserved for holidaymakers but the others were booked out by journalists and they told their colleagues in food and wine about us. It’s terrible, because it was an awful case, but we profited from it.” By the time he and Robin sold to rival chain Malmaison a decade later, they had six hotels. Gerard and his wife Nina opened TerraVina, a small hotel in the New Forest, in 2007; they have just relaunched it as a boutique B&B called Spot in the Woods.

Meanwhile, he was amassing a preposterous number of qualifications and awards – from his MW and MS to Wine Personality of the Year, Industry Legend, an OBE for services to hospitality in 2011, and a slew of Best Taster gongs. He loved the challenge of competitions, he says – “being able to compete really gave me the incentive to learn and to improve. It’s like a sport, you need to practice all the time” – and he was fascinated by the way the wine industry was continually evolving. “In the late 1980s everybody loved the exuberance of New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc; in the 1990s we all wanted full-bodied reds that were rich, rounded and quite extracted. Fashions change but the quality just carries on improving.” Sure, he admits, you can still find awful wine if you really try, but there’s much less of it, and “the technology improves, there are fewer and fewer faulty wines and people are becoming much more knowledgeable.”

He can, of course, take some credit for this expansion of knowledge, via both his own career and the many top sommeliers he has mentored, from Xavier Rousset, who started London’s 28-50 chain of wine bars, to Ronan Sayburn, who is CEO of the Court of Master Sommeliers and Head of Wine at London’s pioneering private wine club 67 Pall Mall. He has also helped to cut through some of the wine world’s excessive formality; just as the Hotel du Vin chain replaced starch with comfort, so Gerard’s style of dining stays focussed on the diner’s pleasure. “Wine is convivial, something to enjoy,” he says firmly. “I don’t want to impose anything. If a table want to drink Madiran with Dover sole, why shouldn’t they? You can offer the benefit of your knowledge but only to people who want it. I always tell young sommeliers not to insist that people have this or that. Some will love wine but some will just want to have fun with their friends, and your job is to help them and not to try to be clever.” And yet, he is one of the world’s top talents at food and wine matching. He is simply a great sommelier: he understands that the dining experience, however elevated, is not supposed to be about him, unless he is the customer.

He is humble, but not self-effacing. He is proud of his MW “because I’m not academic, and those are exams that some people who have been to university don’t pass. And I’m proud of becoming World Champion. I’d come second three times, and was starting to think I’d never get it!” He recognises what the Hotel du Vin chain achieved, and he is also delighted to have been awarded the 37th International Civilta’ Del Vino Prize (International Wine Culture Prize) by Masi. He waxes lyrical about the three days spent at their winery – “They were amazing, we were so well looked after, and the food and wine were sensational!” One of the wine-world evolutions he is enjoying is the evolving attitude to Italian wine: “Once, it was all about Tuscany and Piedmont, but now there’s an understanding of how great the wines of the Veneto can be.” He thinks Valpolicella is still underrated, like so many wines that were beloved in the 1980s. “Beaujolais, Muscadet: people don’t realise how good they are… but they’re all coming back, as they deserve to.” I can’t resist asking: what would he serve with a Masi Amarone? “Probably a slow-cooked meat that is quite tender and rich, like a beautiful stew of wild boar or beef…” But as usual, he refuses to be prescriptive. “If it’s summer, you’ll want something lighter. The most important thing is that the company is good: nobody stops to analyse the wine when they are having a great evening, and that’s just as it should be.” Gerard Basset has dedicated his life to ensuring that people do indeed have a great evening, and so they have, in their thousands, thanks to his charm and expertise. Even for a man as humble as this one, that is surely something of which to be very proud indeed.

FLINT WINES BURGUNDY EN PRIMEUR 2017 VINTAGE

Puligny-Montrachet, August 2017

The morning of the second of January rolls around and we open one eye drearily. January; the dark, bleak month of less alcohol, salad leaves and exercise.

There is one, sole aspect that makes it an enjoyable month. Burgundy.

Ah, Burgundy. Eyes cloud over, a faraway gaze quickly becomes etched.

“Christina?”

“Mmmmmhmmmm?”

“I just asked you a question. Were you not listening?”

“Oh. Sorry. I was just thinking of Pinot Noir and how much I would like to elope with it.”

As I wrote here, my heart is still very much lodged somewhere in the limestone of the Côte d’Or.

January brings with it the opportunity for us city-dwellers to gain an invaluable insight into the vintage to be released later in the year, in this case 2017. I feel the Burgundy en primeur tastings are somewhat more insightful than their (very) distant relatives, the Bordeaux en primeurs, which continue to baffle me (approximate blends and sky-high tannin that don’t come very close to the final wine, no thanks). While tasting young wines from tank or barrel can be difficult, Burgundy is a little more forgiving. Pinot Noir in particular lends us a hand; thin skins and delicacy offer more of a window into both climate and terroir, thus we are able to gain early glimpses into what the vintage will bring. Chardonnay, while perhaps a little tighter, and sometimes a little meaner, is quicker to form and to give its own opinions to us on how it will become. Personified, Young Pinot is the Shy Cute Kid, Young Chardonnay the Defiant Kid, while I would argue that Young Cabernet is the kid in the corner screaming and being difficult.

Of 2017

Speaking to growers, echoes resounded in the room of équilibre: balance. 2017 brought with it regular yields for the first time in a string of lower yielding vintages with frost, hail and rot conditions being the ever-present enemy.

Olivier Giroux of Domaine du Clos des Rocs reminded me, “it is always a question of viticulture, balance comes from working in a balanced manner.” This is true; while vintages can throw balanced years into the universe, they can also throw imbalance, and ultimately it is down to the grower to manage the vintage in question.

The tasting showed me that 2017 is a bright, pleasant and early-drinking vintage, with the wines, especially the whites, really singing at this moment in time. The whites are structured and bold, with tons of energy and balance. They’re incredibly open and honest at this stage but there’s a certain backbone running through them that makes it clear these will cellar.

I was in Burgundy in mid August 2017 for a week and it was hot. It’s not a hot vintage by any means, but the reds are ready and softly plush; much more so than the strikingly zippy and classically acid-driven 2016s that I’m so enchanted by. Nonetheless they are charming, giving and alluring in their bright fruit. Stems brought freshness to several wines in this line-up.

The wines

Flint Wines have one of the most dynamic and well-curated Burgundy portfolios in London. The below are available through their portfolio; please contact orders@flintwines.com should you have queries.

I mention two growers twice; in both line-ups; Nicolas Faure and Thibaud Clerget of Y. Clerget. Both growers had stand-out wines and they are ones to watch; Faure for the wines’ incomparable lift and lightness, and Clerget for the ultimate purity of fruit.

The below were particular stand-outs (in no particular order).

WHITES

Antoine Jobard Meursault Les Tillets: Wonderful tension and that special, inimitable rock salt poise, unique to the wine in question, that is only possible by working in a subtly careful reductive manner. Balancing on the edge of leanness, on precisely the right side of the tightrope. Lemon and lime zest and pith predominant with such length. Truly stunning.

Y. Clerget Meursault Les Chevalières: Elegant and gentle pear flesh, pear skin and hazelnut skin notes, ever so fresh with a lick of nutmeg on the finish. Pure and very true to place, carrying itself almost weightlessly with a vibrancy not always present in Meursault.

Heitz-Lochardet Chassagne Montrachet 1er Cru La Maltroie: Saline and crunchy with real bite; dense and tight-wound; a very exciting future here and quintessentially Chassagne but with real lift on the finish.

Clos des Rocs Pouilly-Loché Révélation: All of the Clos des Rocs wines were singing, and it was a joy to try their sans souffre cuvee. Sparky, bright, energetic; many, many layers here with a delightful almond savoury balance to the delicious, juicy fruit - a real palate journey.

Nicolas Faure Bourgogne Aligoté “La Corvée de Bully”: WOoOoOoH - stop the (wine) presses. Lipsmacking, moreish, damn delicious Aligoté from old vines (1914) in Pernand Vergelesses. Hella yea; this is one of the best Aligotés I have tasted to date and happily danced in glitter on its own in a sea of Chardonnay. Magnificent.

Domaine du Roc des Boutires Pouilly-Fuissé En Bertilonne: Clear, bright, mineral, pure. Quietly confident and any white Burgundy lover’s dream; elegantly classic.

Ballot Millot Meursault 1er Cru Les Genevrières: Such a wine. Snappy, matchstick, white smoke goodness, straight from the womb. This needs time but it’s going to be *very* good and I can’t wait to return to this in a few years’ time. A very promising future for this grower is evident.

Paul Pillot Chassagne-Montrachet: Intense, exuberant, giving, fleshy, fiercely defiant and lifted. Lovely and a brighter expression of what we might be used to from Chassagne with more focus on poise and fruit skin than fleshy notes. Gorgeous subtlety here.

REDS

Domaine Berthaut-Gerbet Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Nuits

From talented young superstar Amélie Bertaut comes this beautiful, perfumed and lifted Hautes Côtes that far exceeds its appellation. Lilacs, peonies and fresh raspberry juice - singing and so bright, a true delicate delight.

Domaine Duroché Gevrey-Chambertin “Les jeunes rois”

There is a reason some domaines enjoy whispers of their names around the trade, and Duroché is one of these for good reason. This is a striking expression of Gevrey; powerful, bold, with real oomph. Fresh cherries rolled around in herbs and spices, with a finish that goes on forever. A stand alone wine.

Mark Haisma Morey-Saint-Denis 1er Cru Les Chaffots

Every now and then you taste a wine that makes you stop and just nod. This was one of them. So much intensity of flavour but without being punchy; there is lift and elegance on the back palate here. Bright black cherry skin, wild thyme and ginger and elegant wild strawberries. Such a fine, clear and certain expression of Morey fruit.

Georges Noëllat Vosne-Romanée 1er Cru Les Chaumes

A wine that speaks of elegance of fruit; subtleties and of the secrets of terroir. Very pure, delicate, but with underlying structure that will keep this wine alive for a long time.

Domaine Nicolas Faure Nuits-Saint-Georges Les Herbues

I was so taken aback when I tasted this wine. It’s rare that a Burgundy knocks me sideways out of pure surprise; this succeeded. A long, semi carbonic alcoholic fermentation (21 days), with ageing in foudre. Very gentle pigeage. The fruit is so pure and vibrant;

Domaine Y. Clerget Volnay 1er Cru Monopole Clos du Verseuil

Another wine from one of Burgundy’s young talents. This, together with the de Montille, provides the quintessential essence of what I deem young Burgundy to be. Transparent minerality, red cherries as picked from the tree, crunchy and pure, with so much more to give, without giving any away; that is the secret to fine Burgundy. This wine possesses that quality.

Domaine des Lambrays Clos des Lambrays Grand Cru

A blast from the past; Boris Champy was the first winemaker I ever worked with and learnt from. To see his first vintage at Lambrays was a joy; spiritual, bright, classic Pinot; tightwound and coiled, waiting to show its feathers with age.

Domaine Henri Gouges Nuits-Saint-Georges Clos Fontaine Jacquinot

Few come close to achieving the Gouges expression of NSG. This cuvee, its first debut, exceeded even itself. With the deep underbelly of Nuits-Saint-Georges and its bramble edges, this has a certain elegance to it and speaks of floral notes; of lavender and wild flowers.

Domaine de Montille Volnay 1er Cru Les Mitans

As with the Clerget above, this speaks of Pinot Noir in Pinot Noir’s essence. Fragrant as fragrant can be, with finesse and poise that makes me wonder whether the extent of these characteristics is unique to Volnay. When I close my eyes and envision Burgundy, this is what I see.

Domaine Confuron Cotetidot Vosne Romanée Les Suchots

Wow. Vosne with broad shoulders; this is a wine with rumbling depth, power and energy; a wine that will outlive us all. Crunchy wild blackcurrants and wild strawberries with earthy, mineral tannin structure. 100% whole bunch is always employed at this domaine and together with later picking, provides these wines with an immense power-balance-freshness scenario. I was quite bowled over by this, and while I’m not sure it’s the wine to drink right this second, there is something immensely singular, marked and, simply put, special here. Quite remarkable.

GUT OGGAU FAMILY REUNION ROSÉ 2016

Rosé doesn’t have to look like it’s just come out of a paint catalogue selling various hues of pale pink, ergo this post on what I deem to be one of the finest rosés in the world.

Indeed; that word, “rosé”. What do we even mean by that? Isn’t it a shame that our market has become dominated by almost only “pale, shimmering rosés that bring you back to your time holidaying on the Côte d'Azur”? Pur-lease. What’s worse, there is a whole generation of drinkers who don’t believe in darker shades of rosé because they assume the wines will be sweet (bad White Zinfandel is predominantly to blame for this).

The rosé segment, or should I say, the direct press red segment, has so much more to offer than “nice” pale rosé the colour of “pretty petals with a hint of salmon.” Yes, these wines serve a purpose and are enjoyed, and granted, you don’t have to think about those wines as much, but the segment also has wines that are capable of much thought and deep contemplation. Wines of intellect, of wonder, that surpass vinous segmentations. Wines that are able to speak of a place, exactly as this one does; the Burgenland.

I first tasted this wine with its makers; Eduard Tscheppe and Stephanie Tscheppe Eselbock, in their wonderful home in the depths of the Burgenland. Not only does this family make wonderful wine, they are incredibly kind, welcoming and full of love for life. We drank it at dinner and it made me stop eating and marvel at the contents of the glass for many, many moments. I had never tasted anything like it, and the colour of its contents radiated from within the glass. The wine was alive, and it was definitely speaking.

Eduard and Stephanie and the family reunion rosé, January 2018

Gut Oggau Family Reunion Rosé 2016, Buon Vino, £48 / via their importer Dynamic Vines

30-year-old vines; Zweigelt, Blaufrankisch, Roesler from limestone, slate and gravel. Hand harvested, destemmed, direct press with a couple of hours on skins. Fermentation in 500, 1,000 and 1,500L barrels. Aged in 500L barrels for eight months. Bottled unfined, unfiltered, with no sulphur addition.

Imagine picking cranberries from a cranberry bush, rolling them around in a bowl of fresh earth, thyme, rosemary and white pepper, blowing off the remnants into the cool summer air, crushing some raspberries with your forefingers to attain the juice only, gently breaking the cranberrys’ skins with your teeth, enjoying the fresh rush of acidity that comes with it and licking the raspberry juice from your fingers. That’s how this wine tastes.

It is the tale of a difficult vintage, but one of eternal optimism where two vineyards become one through the mergence of the Winifred and Josephine cuvees (nearly all of Josephine was lost due to frosts and hailstorms).

It is a reminder that in life, we can be optimistic or pessimistic, but that the best results are born from optimism, hope and determination.

2019: Predictions

As we are about to pop the cork to 2019, I find myself thinking about the current state of the wine trade in the on-trade and indie sector in the UK, particularly London. I am not going to address Brexit.

We have never seen so much diversity in terms of wine as today; the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. This means a competitive and somewhat flooded market, but there is always space for interesting new quality-driven wines and the increase in small, grower-focussed importers is testament to that (you know who you are - Flint Wines, Keeling Andrew & Co, Newcomer, Uncharted, Kiffe my Wines, Under the Bonnet, Modal, Nekter, Otros Vinos, the list goes on…) You guys rock, and London’s wine scene would shine far less brightly without you. I can’t write this without mentioning veterans Les Caves and Vine Trail, and the original Richards Walford, who were some of the first to light the flame - you have inspired others to do the same and you keep fighting the good fight.

2018 has seen Mass Twitter Debate about the never-ending topic of innovation. I could write an essay on this, but my own stance can be summarised in one sentence:

Let’s welcome innovation when it focusses on quality, terroir, and purity of expression (e.g. eggs!), but please, let us not put our wine in whiskey barrels - this is not the future of wine.

So, hopefully we won’t see whiskey barrel (et al.) wine making an appearance in 2019, but what will we see?

Last year I wrote this, where I scribbled my predictions for 2018: (more) Gamay, The Return of the Rich White, the darker rosé, Greece, English still wine, the Savoie, Armagnac, Canada, Grower Champagne and New Wave wines. I think it’s safe to say now that we’ve had a boom of all of these categories in the on-trade and independent sector, save except for Armagnac. I think this was more of a personal dream, although I still think there is space for more artisan-led spirits in the market. I’d drink them.

I believe we’ll see continued growth for all of these wines, joined by:

Still more Gamay. Yep, couldn’t resist. It’s global domination time.

More Alpine wine! Bugey, Isère, Coteaux du Grésivaudan, Geneva, etc. As we have such an increased interest in the Savoie, I believe we will see more and more interest in the surrounding viticultural areas. This will be mainly for Mondeuse, but very much also for the whites and for lesser-known reds. I clearly remember discussing Persan at the Ampelographic Conference in 2016, and it was still very much a dream that Persan would become a grape variety on the tips of everyone’s tongues. Yet here we are, with Persan listed in many of the top restaurants of New York, and some in London. What’s next? Etriare de la Dhuy anyone?!

SIDE NOTE: we need to study these regions carefully. How bloody confusing is it that Mondeuse is named PersanNE in a Bugey dialect? WTF?

More Chenin! Yes, we’ve been #CheninCheninChenin - ing all year now (I returned twice to Racines to learn from our Chenin Queen, Pascaline), but this is in no fear of slowing down. Aside from the obvious French and South African examples, where we see an astounding number of small, terroir-driven growers that are thankfully taking more and more space on our lists, California is starting to knock at the door too. Australia and New Zealand - show us your grower Chenin (please!) The likes of Jauma, Shobbrook and Millton exist, but there is definitely space for more.

Side note: as I write this, Imogen Taylor of Nekter Wines has mentioned that she and Jon are considering Geyer Wine Co’s minimal intervention, no SO2 Chenin. Snaps for Nekter!

More pepper. We’re all Northern Rhône nuts, there’s nothing new there, but I think we’ll see even more pepper wine popping up next year. Let’s get #Rotundone trending, and more Pineau d’Aunis, thank you.

Side note: will we start to see a differentiation of Serine vs Syrah on lists? I’d like that.

Sake! We’re a bit behind New York here (cough, harumph you say, but it’s often true). My introduction to sake there made me ponder whether we’ll start to see more in London. As if by magic, I stumbled upon the Kanpai sake brewery in my ‘hood, Peckham. Small batch, natural and bloody good. Hats off to them, hopefully this is the start of London’s #sakerevolution

New York State: Disclaimer: I’m biased as I’m working on a campaign for them for Westbury, but regardless of this bias I was beyond impressed with what I saw on a trip in August. Small, terroir-focussed growers doing beyond epic things with both vinifera and hybrids. FLX Riesling, Blaufränkisch and hybrid petnats, please!

Side note: I am certain that carefully made, terroir-conscious hybrids not just from NYS but from across many regions will start to appear on lists more within the next five years.

Indigenous grapes, from everywhere but especially from Alto Adige (niche but I hope so). Alois Lagader has given us a head start with their Comet series: Moscato Giallo, Blatterle, Fraueler, and Versoalen please?

US wine: further afield…? Will we start seeing “other” states make more of an appearance? Idaho, Virginia, Maryland? Pennsylvania? There is much to explore on US soil.

Mexico! Tresomm’s Aligoté proved to me that truly anything is possible in our world of wine. The Mexican wines in the UK petition starts here.

New World Gewürztraminer. “You what now?!” I hear you cry. I’m still to taste many I like, but the Gewürz from Bloomer Creek completely and utterly blew my socks off. Scrap that; it blew my socks off so hard that they combusted into milions of tiny pieces of cotton. It’s a world class Fine Wine. I fell in love with a Gewürz! Who would have thought. If they’re doing it, is someone else too? Show yourself, please.

And for me? Write even more, as Hugh Johnson says, “Always scribble, scribble, scribble.” Not every post has to be 2,000 words and perfect. Keep learning, keep writing, keep studying, keep tasting.

HNY!

BOJO 4 LYF

Domaine Dujac: 2017s with Diana Snowden-Seysses

I caught up with Diana Snowden-Seysses in October whilst on a brief pit-stop in Burgundy. Diana herself was just back from Napa, as she balances her work according to Mother Nature’s harvest times via Burgundy and Napa.

I stand with her in the cellar in Morey-Saint-Denis, where we get ready to taste the 2017s from barrel, which are just about to be racked: a good time to taste. It’s her first time tasting them since June. She says, “Closing the bung for a while helps me to not intervene. It’s important to let the wines become what they want to become.”

We taste extensively from one year old barrels, all of which (apart from some experimental Stockinger additions) are from the Rémond cooperage, which the domaine has worked with since Jacques’ very beginnings. They have refined and crafted their signature toast over many years; a long toast over relatively low heat, which give a slightly sweet structure to the wine. Diana muses that while the barrels still create their Dujac-stamped wines, vintages (and thus fruit) are getting riper. Global warming is very real.

“Global warming is changing our oak regime. Jacques used 100% new wood, whereas we are reducing that to 40% for villages and 70-80% for premiers and grands crus.”

The oak regime at Dujac is the ultimate partnership, even mastery, of wood and wine, and this is the ultimate example of human intervention to guide soil, vineyard, plant and climate to show its utmost capacity for wine. Often in wine, we omit one key factor of terroir; human interpretation. Dujac is an exceptional example of the human hand aiding terroir, as Diana muses, “wine is the ultimate form of human civilisation.”

Each barrel we taste has backbone, guidance and a structure, allowing the fruit to express itself in its purest form. This is what the carefully skilled work of the cooper, and many examinations of barrels and listening to the results, gives to a wine.

SO2 is kept low, and Dujac was one of the first domaines to trial UV lightbulbs for sterilising barrels instead of sulphur candles, enabling the domaine to avoid residual sulphur in barrels.

The Vosne-Romanée 1er Cru Les Beaux Monts showed crunchy, bright, fresh but dense with cherry flesh, with such lift and raciness. Tense and bright with a shadow of poised, smoky reduction; this has an exciting future.

Diana muses that it’s important to walk the line of reduction; a pure form of reduction that comes from fine lees and environments poor in oxygen.

We study the Vosne-Romanée 1er Cru Aux Malconsorts “four ways;”

1. From one-use Rémond barrel – this seems more mineral, with a crunchy, earthy core, but light footed and with such length and gentle floral tones. The sort of wine that makes you question and look deep in the glass. Diana says, “Yes. I love wines that you have to go and find.”

2. From a new Rémond barrel – so beautifully integrated; oak and wine; a supportive marriage. A high tone wine – bright, dense cherry skin, more closed and tightly fisted with a smoky, ashy edge.

3. In Stockinger, “Y+” - a soft, textural component. Slightly broader shoulders, a little more oomph here, with some subtle reduction – definitely still in early stages of its life, still figuring itself out.

4. In Stockinger, “Y” – open, pretty, giving in its red fruits; plums, raspberries and cherries upon cherries. Fleshy and so pretty, with a floral, peony edge. Diana muses that this feels more Dujac.

Charmes Chambertin

A cooler profile; raspberry skin, perfumed notes; irises and rosehip with an underlying serious, stony, almost iron-like side. Still rather tight fisted.

Echezeaux

This took my breath away; very much a being of its own. Ephemeral, gentle, flirtatious and shy, all at the same time. A wine that carries different notes with every aroma; a song that gives different meanings every time. Bergamot and lillies, lavender, earth and white truffle. Imagine peonies held hands with wild strawberries and have a dust bath together with a sprinkling of wild herbs.

Clos St Denis

A darker fruit profile here, somehow more brooding. Black cherries and gentle mint with rosemary and undergrowth, met by cherry stones and a lick of graphite. Earthy and deep, still hiding a little.

Clos de la Roche

Lifted, with prominent blood orange and orange rind on the nose; a beautiful and bright partner to the perfumed cherry flesh. Distinct minerality on the palate, zippy and textured; very fine tannins led by a mineral, gravelly, gently dusty profile.

Bonnes Mares

Tight, white smoke profile. More reductive at this stage. Violets, lilacs, wet earth, olive tapenade and savoury, herbal elements. Some real grip, with a brisk edge, this is going to be quite something when it comes into its own.

2016s, bottled wines

“I love the energy of the 2016 wines,” Diana says.

Vosne-Romanée 1er Cru Aux Malconsorts 2016

So bright and youthful, a youngster seeing the world through its own eyes for the first time. A herbal approach – thyme with cherry skin. There is a distinct crunchy stoniness on the mid palate with a lifted, scented edge. Rosehip oil with fresh roses on the finish. Elegant and delicate.

Diana notes, “it took me ten years to really love Malconsorts. It is elusive, hard to pin down. Beauxmonts is more obvious; they are dense wines. I think it took ten years of biodynamics to get these vines to really show their stuff.”

Clos St Denis 2016

Bright red cherries and violets, peony petals and juicy bramble berries, even with a lifted grapefruit edge. There is a delicate floral profile of dried roses and persimmon. So textural on the palate; plush, silky, satin-like, with delicate fine grained tannins.

Clos de la Roche 2016

Cloves, blood orange and ripe cherry fruit, fleshy and giving lots early in its life. Nutmeg joins on the palate, with a juicy, sappy core of fresh cranberries, with delicate earthy tones of undergrowth and tobacco. A lifted finish of exotic spice and frankincense and liquorice.

Whole bunch here tends to sit at 80%, whereas for the Romanée-Saint-Vivant and Les Gruenchers the domaine carries out 100% whole bunch, due to the ancient vine material giving small clusters and small berries.

We discuss the role of stems in winemaking. Due to the potassium in the stems, you lose tartaric acid in the wine, but the stems give the ever-important freshness and lift to wine. Therefore, even with lower acid in hot years, the wine is capable of lifting itself and of showing its floral, perfumed side. The bunches give explosive and beautiful aromatics; for Diana this scent is home.

Diana ponders on our conversation and disappears back into the cellar, resurfacing with a bottle.

“I thought on the topic of stems we should taste this.”

It is Echezeaux 2003.

2003 was hot. Due to the early nature of the vintage, the harvest crew had not yet arrived, so it was Diana and Jacques in the cellar, and Jeremy in the vineyards. Diana laughs, remembering;

“There were only eighty five days from flowering to harvest, usually it is 100. I spent the vintage on the forklift! It’s the only year where we did everything with 100% whole bunches. Cleaning the destemmer would have been too much to cope with!”

It is deeply perfumed, light on its feet with underlying deep, rich bramble and black cherry fruit. A side of dusty roses and peonies lifts the wine and helps it to dance on the palate. There is some white pepper here, with bergamot and rose oil, finishing on undergrowth with a wild, mossy character.

It is the perfect example of the potential of stems. Even in one of the hottest years of the past two decades, 100% whole bunches here give this wine such lift. When hot vintages, winemakers risk jammy fruit profiles, but stems offer the fruit a hand to the dance; carrying the wine and adding wild dimensions that leave you seeking descriptors in the glass.

Drink Like a Scythian with Abe Schoener and Rajat Parr

The Scythians: Abe Schoener and Rajat Parr

I have experienced several momentous vinous moments in my five-year-long career. If I sat down with all my tattered notebooks and bundles of tasting sheets, I could count over fifty wines that have been wines of a decisive, consequential or even life-changing and opinion forming nature.

There are the wines that have made tears threaten to cascade down my cheeks; the age defiant, deeply honest and utterly unpretentious 1989 Guy Breton Morgon wines of the world. There are the wines that have tapped at my mind’s door, startling me and begging me to consider entirely new and unexpected realms of possibilities; the Jean Pierre Frick sans souffre vs 10mg/L Steinert Grand Cru Riesling 2012 duos of the world; a set of what could be defined as vinous fraternal twins. They remain deeply embedded in my mind. There are the winemakers whose work and whose wines are so vitally entwined with the viticulture of their region that you just want to grab them and thank them for simply existing and for advancing the modern-day world of wine in ways nobody could imagine possible. These are the Rod Berglunds of the world.

It would be an impossible task for me to single out one of them; I would be committing infidelity to the others. There is, however, one recent gathering of friends that makes my thoughts whirl, and indeed a new categorisation for wines that I have adopted, while not always on paper, at least in mind.

Rewind to the beginning of July. I find myself sitting in a room bathed in red; not just any red, but a rumbling, reverberating red that fills the room with a deep hum of energy. I’m in London’s Mandrake Hotel. I am about to sit down and Drink Like a Scythian with Rajat Parr and Abe Schoener.

Mid discussions - Raj Parr, myself, Angelo van Dyk bathed in red